How to Strengthen Your Innovation Pipeline

Originally published May 2020

Even as stay-at-home orders lift and businesses reopen across the country, expectations for innovation investment remain subdued. By now, savvy innovation leaders will have already made proactive adjustments to their activities, turning their focus to Horizon 1 and making themselves indispensable to the business units. Early-stage strategic marketing efforts will have been redirected to support near-term, division-led opportunities while speculative projects are sent to the 2021 back burner. Expert after expert is offering the same advice: use this time to buckle down, reevaluate strategy, trim the fat from your portfolio, and focus on execution rather than exploration – because if you don’t cut back on at least some of your big, non-core bets, someone else will do it for you.

This doesn’t mean you have to tighten the belt completely. Progressive executives recognize the importance of maintaining a certain level of spend across longer-term development initiatives to maintain competitive edge. Not all resources are fungible, particularly in technology-intensive R&D departments where highly specialized scientists conducting fundamental research cannot be readily redeployed to solve a manufacturing scale-up problem, but that doesn’t mean they aren’t worth keeping around. A C-level executive at a Fortune 500 advanced materials company recently acknowledged that they “cut way too far in 2008.” Having slashed budgets for every non-core initiative during the last recession, the business fell behind in several key technology areas, and is still playing catch-up over a decade later. “We won’t make that mistake again,” he insisted.

Maybe you’re reading this as you, like this executive, attempt to keep a large chunk of your portfolio intact. Maybe you’re already under severe austerity measures, but are thinking ahead to a time when you will be able to expand your portfolio once more. So, how will you decide what to keep (or, if you’ve already made big cuts, what do you add back in first)?

First of all, it’s important to make decisions about investment priorities on a program-by-program basis – not by scraping the top off across the board. William Banholzer, former CTO of Dow Chemical Company, explains: “To reduce spending in times of crisis, the most common strategy is the classic haircut: a small cut in overall funding across the entire project portfolio, for instance, a 10% cut from every ongoing project. But […] a better strategy is to cut 100% of the least attractive 10% of programs.” In the latter strategy – which he calls the “lifeboat” approach – you’re either in or you’re out. Some feathers may be ruffled but, as Banholzer notes, “It is impossible to imagine a scenario in which it would be a good strategy to sacrifice the top programs in any way to keep the bottom performers on life support.”

The first step in implementing a “lifeboat” portfolio strategy is to get rid of the obvious candidates for termination – the vanity projects, the expensive tech push activities, the stuff that no one has bothered to get rid of even though it has yet to generate revenue, etc. This process, often referred to as “killing zombies” in the innovation community, is a best practice even in good times and is extra important now. However, for most folks, it won’t be enough. Unless your business is in one of the few sectors that has seen increased activity during the pandemic, you’re probably facing pressure to put at least a few promising programs on the chopping block.

To distinguish not just between “good” and “bad” but also between “good” and “necessary,” you’ll need to take a really hard look at your investments – possibly through some new or different lenses. These screens will necessarily vary from organization to organization, and many of the usual factors will still apply, but given the current and future uncertainty all innovators are facing at the moment, we believe that there are four less common, but important, factors that should be given particularly strong consideration:

- The problem-capability-vision connection

- Speed to market testing

- Industry clock speed

- Option value

The Problem-Capability-Vision Connection

We would argue that this is one of the most important criteria for project selection at any time, but it is particularly crucial in the current context. If you cannot prove that there is a meaningful problem to be solved with clear relevance to both your capabilities and your strategic objectives, you should seriously reconsider the investment.

Presumably, by this point in the crisis, you’ve already revisited your organization’s objectives and performance targets. You have adjusted your expectations. You have defined a new version of what you intend to accomplish over the next 1-3 years. If you’ve already started using this revised viewpoint to weed out investments that no longer seem well-aligned, great; if not, get started there right away.

Meeting revised objectives and performance targets will require adjusting the “mesh size” of your portfolio screening approach.

As you consider high-level strategic alignment of various innovation programs, pay close attention to the interplay of market needs and organizational capabilities embedded in each. Be ruthless about cutting programs that (a) don’t focus on real, urgently felt customer problems and/or (b) don’t leverage your differentiated technical and commercial competencies. This is not the time for impressive “tech push” efforts or innovations being pursued for their “cool” factor or to generate visibility.

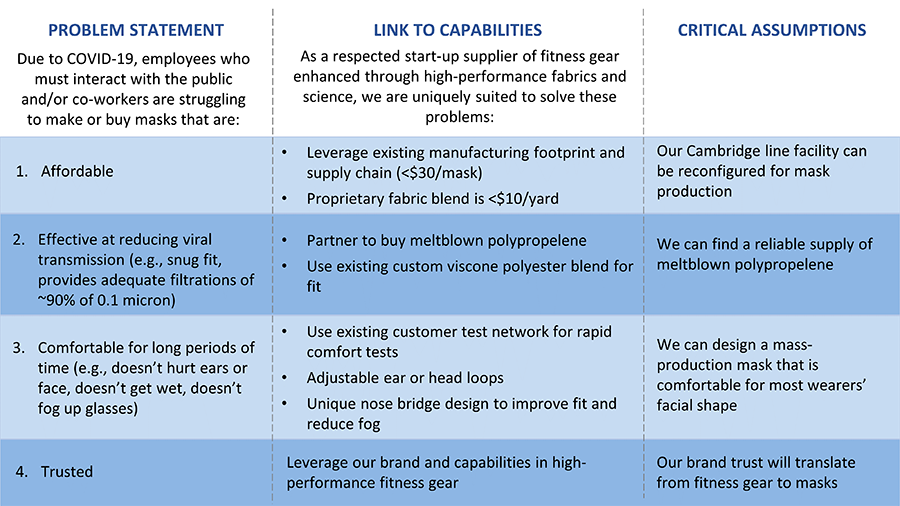

Not sure how to test whether or not you’re solving for a real pain point? Uncertain whether you really have the best play? Here’s what we’d suggest, based on the approach used by a Fortune 500 advanced materials company in our network:

- Write a clear customer problem statement that you and your peers believe in.

- Diagram the problem by breaking it down into its component parts.

- Map those problem components to your capabilities. Objectively speaking, does this program fit within the core of your organization? This is where you have an edge over competitors and where innovation investments are most likely to payoff.

- Identify the critical assumption(s) around each problem-capability link. If there is substantial uncertainty in any given area, define what you need to do to learn more and move quickly to resolve it or kill the program.

An illustrative problem-capability-assumptions map.

Speed to Market Testing

At any given time, innovative companies often have at least a handful of product or service offerings in development that they are reluctant to discuss freely with customers and end users – usually because they feel uncertain about the strength of their IP position or the uniqueness of their solution, and they’re worried that competitors will catch on and catch up. There is value in circumspection, and there are paths to commercial success that don’t require airtight patenting or breakthrough inventions, but now is not the time to keep your ideas to yourself.

The problem is that if you don’t test your concept properly in the market, you have no way of knowing whether you’re addressing a real, urgent issue in a way that people are willing to pay for – and so you run a very high risk of getting far down a development path that ultimately yields nothing. A client of ours spent years and tens of millions of dollars investing in a processing technology that produced a new product with performance no one else had ever achieved. Unfortunately, while the process itself was clever, it was not actually all that hard to replicate, and our client feared that competitors would move fast to copy it the moment they saw a prototype.

To protect against this possibility, our client kept their plans mostly in-house, investing in and scaling the technology with very little downstream input. Finally, when they felt comfortable that they had a big enough head start to win, they began engaging their customers, excited to show off what they’d achieved. To their dismay, the market response was lukewarm – while their improved product met some niche needs, it was overengineered for all the largest market segments they’d hoped to target. Eventually, they killed the program.

Maybe our client would have had success if they’d been trying to enter a less commoditized market. Maybe they could have had a breakthrough if they’d spent just a little more money trying to optimize their process. Maybe in a few years, a new megatrend will shift the industry tailwinds, generating demand for exactly what our client can provide. But there’s no way to know, and right now, there’s no way to justify the risk of taking on such intense uncertainty.

As you look across your portfolio, ask yourself – can I go out and test this idea with my customers right now? Or do I need to keep it under wraps a little while longer? If your answer is the latter, think about shifting your attention and resources to a different idea.

Industry Clockspeed

This factor may not be relevant across the board, but for B2B companies in particular, and for materials and chemicals companies especially, industry-specific commercialization timelines may be another important consideration in deciding what to hold onto and what to cut loose. If you sell your base technology into a wide range of applications, consider skewing your focus toward those that have the fastest turnarounds, at least for the moment. The efficiency of your portfolio and your ability to generate near-term revenue will be critical to recovering from this crisis; placing a big bet in a market where it takes 7+ years to spec in a new part probably isn’t the move.

For example, say you have a deep materials competency that you leverage across dozens of end uses. You currently have a couple innovation programs that are candidates for the chopping block: one that would supply a novel consumer electronics component, and one that aims to serve the pharmaceutical industry. The latter opportunity promises high margins if successful, but the pharma industry is slow to develop – the customer base and regulators set the pace, and they can drag their feet for years. The consumer electronics opportunity, on the other hand, is immediate. It might not offer the same longevity or profitability, but you’ll know whether you’ve got a winner far sooner.

This isn’t the only factor to consider, nor is it the most critical, but if reducing uncertainty is a key goal of yours – which at the moment, it should be – industry clock speed may be a useful lens to apply.

Option Value

Reopening of the economy aside, intense uncertainty will likely persist for the foreseeable future. The commercial indicators you are accustomed to using for guidance (customer pull, market size and growth, etc.) may become temporarily less reliable. Flexibility is a critical attribute in times like this, not just in terms of your mindset, but also in terms of your portfolio, and investing disproportionately in programs that give you options – either inherently, or because they add a new dimension to your portfolio – will make it easier for you to pivot and weather the storm when new challenges inevitably arise.

It’s no secret that spreading your bets across several options is key to building a resilient portfolio; that investing for options hedges against uncertainty and de-risks individual investments. As Rita McGrath wrote in 2008, “In highly uncertain environments, it’s nearly impossible to predict with any accuracy which innovations are likely to succeed and which are not. It makes sense, therefore, to test out a number of different approaches on a small scale, proceeding forward only when you’ve validated enough assumptions to move ahead with confidence.” Unfortunately, placing a bet of any size – let alone multiple bets – requires resources, and for many companies, those resources are currently in short supply.

As such, now may be a good time to consider whether you can identify option value at the level of the individual program – not just in looking across the portfolio in its entirety. As with industry clock speed, this factor may not be equally as meaningful for every type of company, but for some, it’s worth thinking about how a single innovation could position you for the future. Say you have a choice between working on a highly specialized product for a narrow customer use case or a software platform that has the potential to impact your offerings across multiple business units. All else being equal, the latter is more likely to generate long-term value for the organization – because, in the vernacular of Antifragile author Nassim Taleb, it provides more “off-ramps” on the highway of innovation. Again, this isn’t an end-all, be-all criterion, but it might be a useful tie breaker.

None of these criteria – except perhaps #1 – can or even should replace more traditional portfolio prioritization methods. Well-established best practices for disciplined portfolio management still stand, and applying those practices is a critical first step in prioritizing where to focus during this time. However, we also anticipate that many organizations will need to get both more specific and more creative in their evaluation of new and existing programs as they attempt to ride out this very unpredictable wave.

The four screens suggested here – strength of connection between problems, capabilities, and vision; speed to market testing; industry clock speed; and optionality – are just a start. We’re curious to hear from you! What criteria will you consider differently in the coming weeks, months, and years?

This article was co-written by Bryn Adams.

Find out how Newry can help your organization find high-value options for growth. Expand your pipeline before it runs dry.