At 8:12AM on July 20, 1976, NASA received the signal that the Viking 1 had made the first ever successful landing on Mars. For more than six years, Viking 1 roamed, collecting the first ever soil samples from the Red Planet and sending back the first ever photos from its surface.

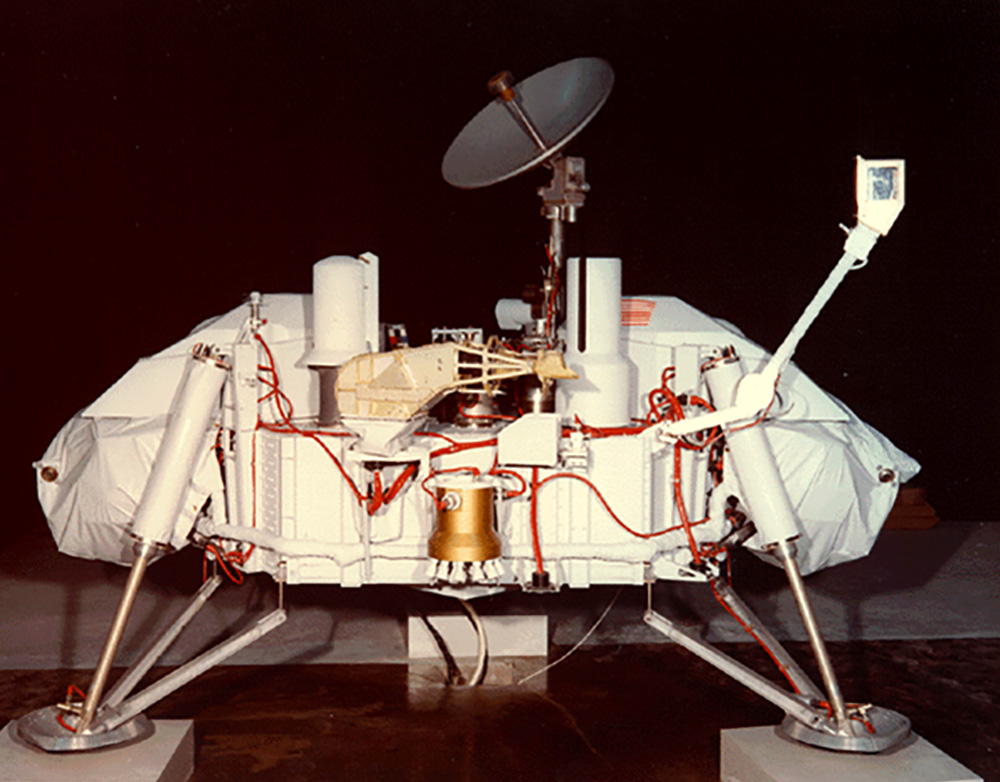

A model of the Viking Lander (NASA)

What many people do not know is that the landing was made possible by a lightweight fibrous material developed for NASA by DuPont. Without this material – which is five times stronger than steel on a pound-for-pound basis – lining its parachute shrouds, Viking 1 would have crashed, and this pioneering exploration wouldn’t have happened.

For DuPont, however, the Mars landing was just the beginning. When word of DuPont’s invention reached Goodyear Tire and Rubber Company, Goodyear decided to incorporate the material into its radial tires, increasing tread life by 10,000 miles. Today, this innovative substance, which started in an extremely niche application, has become a critical part of everyday transportation.

In early-stage innovation, the question of whether to pursue a strategy of “tech push” (i.e., developing a technology and then finding a customer) versus “market pull” (i.e., identifying a customer need and then developing a technical solution) is a classic – and contested – one. There are myriad examples of success (and failure) associated with both approaches, and Newry’s clients have faced challenges on both sides of the fence:

- Lack of Need: Recently, Newry worked with a client who had developed a novel material for the energy industry. This material offered significantly improved performance over incumbents, but Newry found through surveys that there was limited pull for our client’s innovation. Unfortunately, users did not need or care about a better-performing version of this particular material – what they actually wanted was innovation in a different part of the system

- Lack of Technology/Capability: On the other side of the spectrum, we worked with a client who successfully identified an urgent customer need for improved mapping and imaging of surgical procedures, but did not possess the core competencies required to resolve the key technical issues. Despite high interest, our client lost out due to a lack of relevant capabilities

One could argue that DuPont’s experience with Viking 1 and radial tires is a rare example of a company navigating this dilemma successfully by first following market needs (developing a groundbreaking material on NASA’s behalf) and then pushing technology into the market (selling an already existing innovation to Goodyear). But the reality is a little more nuanced:

- DuPont responded to a market need that was urgent, specific, and real… and related directly to their already existing world-class technical expertise in polymer science

- Having created a revolutionary technical innovation for a vital but ultimately limited application, DuPont found an adjacent opportunity that was bigger, fast-growing, and longer-term… and had a clear unmet need for the value DuPont’s material could deliver

Thus, the true moral of the story is that the “tech push vs. market pull” debate is a false dichotomy – or, at the very least, an oversimplification. Technologies do not exist in a vacuum, and neither do market needs. DuPont’s ability to address the initial market opportunity with NASA depended on their technical capabilities – and their ability to derive additional value from their existing technology depended on exploiting unmet market needs. As such, rather than starting from either technology development or market insight, and then trying to find connections later, innovators should be looking for intersections of the two – areas where problems have gone unsolved and their specific set of core capabilities would be valued.

Find out how Newry can help your organization find high-value options for growth. Expand your pipeline before it runs dry.