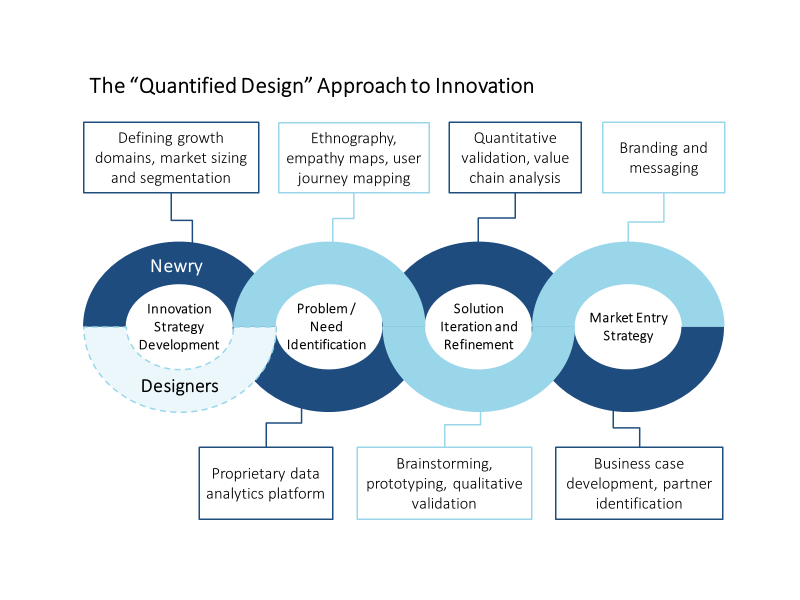

QUANTIFIED DESIGN™: An Innovation Approach Design Thinking

The crowd shouts and cheers its suggestions and encouragement as iconic host of Let’s Make a Deal, Monty Hall, asks the contestant to pick between doors #1, #2, and #3 for the chance to win a prize. Once the contestant has made a choice (let’s say Door #1), Monty ups the suspense by revealing the undesirable contents behind one of the doors not chosen (let’s say Door #2) and asks if they would like to change their selection. At first blush it seems like even odds between the two remaining doors, and all the contestant can go on is their gut and the roar of the crowd – but in this case, a little quantitative analysis can go a long way in solving what has been deemed the “Monty Hall Problem.”

©1971 ABC Television

Many innovation leaders are put in a similar position as the game show contestant – forced to make decisions in a truncated timeframe, with limited data, and under pressure from stakeholders who often possess nothing more than a strong hunch or personal bias to inform their own position. Given their predicament, it’s no surprise that bold bets are questioned, limited, or back-burnered in favor of nearer-term, easier-to-realize opportunities – even if they are smaller and transactional rather than breakthrough and transformative.

In response to this situation, innovation leaders – particularly at consumer products companies – are increasingly turning to design thinking as a strategy to surface, iterate on, and develop products targeting growth markets. For companies that do not have the luxury of a significant central research budget and long development timelines (and even some that do), design thinking offers innovation leaders a rapid, highly user-focused approach to support bolder, longer-term bets.

However, while the design thinking process is an excellent method to identify potential opportunities and the depth of the associated problem, it has a couple of common failure modes:

- Solving “A” Problem, Not “The” Problem: While a great deal of divergent and convergent thinking goes into the development of a design thinking solution, the mechanism for deciding which problem to solve in the first place is often less robust. Designers excel at identifying unmet needs, but their process typically lacks rigorous quantification and comparison of the relative size, growth, and overall commercial promise of those opportunities. As a result, prioritization of where to focus tends to be ad hoc.

- Market “Blinders”: Designers are deeply focused on the user experience. They have a unique ability to understand the nuances of unresolved pain points, which allows them to produce elegant solutions. The downside of this singular focus is that it often doesn’t consider the economic realities of the ecosystem that surrounds the end user. Any investigation of supply chain dynamics – location of profit pools, relative decision-making power of various stakeholders, etc. – usually takes place toward the end of the process, if it happens at all.

- Incomplete Business Case: Together, these gaps may result in a beautifully crafted product but an insufficient understanding of which version of the solution meets revenue and timing targets. Unfortunately, these open questions don’t become obvious until the proposed innovation is well down the path toward commercialization, at which point it is often too late to make any major adjustments without significant additional investment. This scenario causes immense headaches for the business unit and creates the potential for internal backlash.

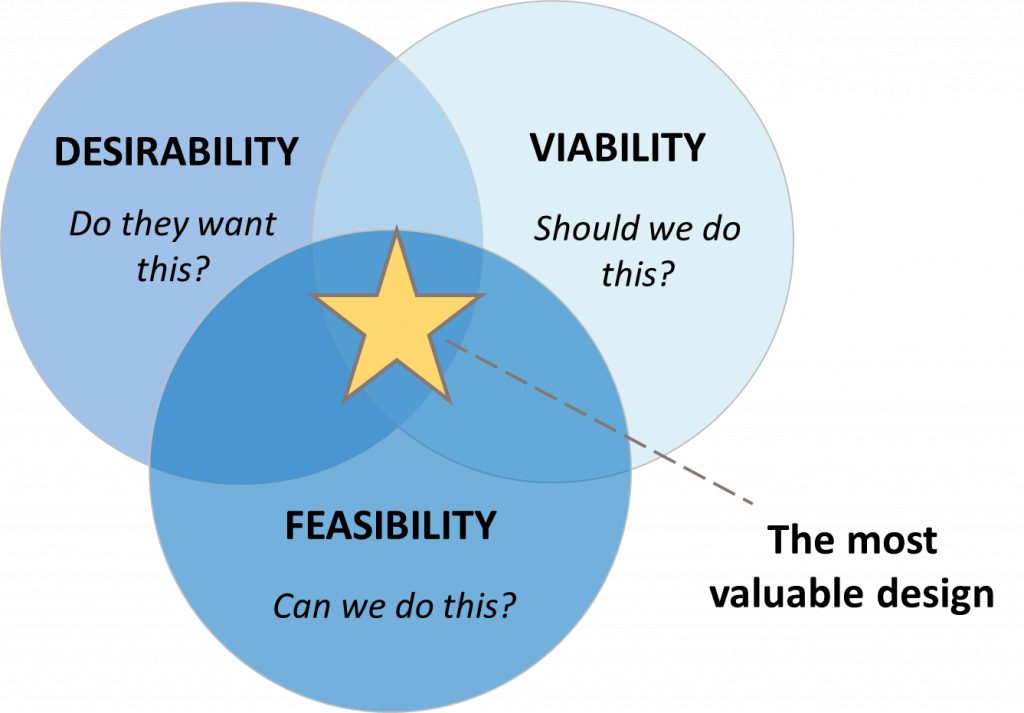

Desirability/Feasibility/Viability framework part of the QUANTIFIED DESIGN™ innovation process

All of these issues tie back to an imbalance in the “Desirability/Feasibility/Viability” framework that many design firms use to describe the key elements of a successful innovation. In theory, all three of these components should be explored at every stage of the design thinking process; in practice, Viability often gets shortchanged, especially early on.

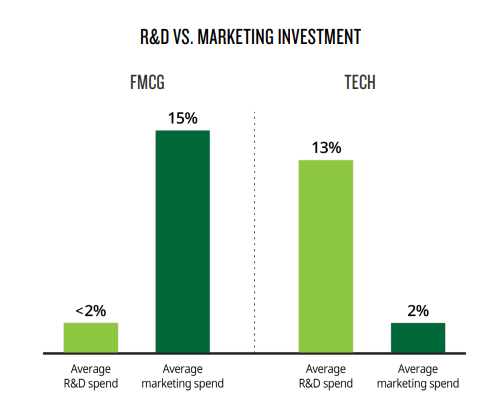

Product companies in particular sometimes rush to get to the testing phase, shortchanging strategic focusing efforts and truncating the activities devoted to market testing and critical analysis. In fact, upfront product investment for fast-moving-consumer-goods (FMCG) companies significantly lags that of the fast-growing tech sector, with Nielsen noting that “FCMG brands should spend more time developing and refining their value proposition.”

Source: Setting the Record Straight on Innovation Failure – Nielsen Company, 2018

We’ve found that when brands race to start prototyping instead of investing in understanding their product’s value prop and the dynamics of the market they’re trying to enter, the result is often a solution users love, but no one will buy.

This is especially true in B2B situations involving differing value props between the end user and others in the value chain. Recently, for example, Newry was brought in to identify potential partners to take a new healthcare product to market. The product, developed through a rigorous design thinking process, was thoughtfully engineered and addressed a real end user need. However, our initial analysis indicated that several key issues (including questions around price point, likely purchasers/channel, and implications of the product’s success) remained unsolved. These were areas of high importance to players in the supply chain but had been missed due to a focus on solving the end user’s problem.

Given the notoriously convoluted value chain dynamics of the medical industry, we realized building insight around these unknowns was a higher priority than finding a partner for commercialization and pivoted to develop a quantitative understanding of the device’s value within the context of the entire healthcare ecosystem. The findings from this work helped the client refocus their go-to-market strategy on more realistic targets – a valuable outcome, but one that would have been more useful to understand from the beginning.

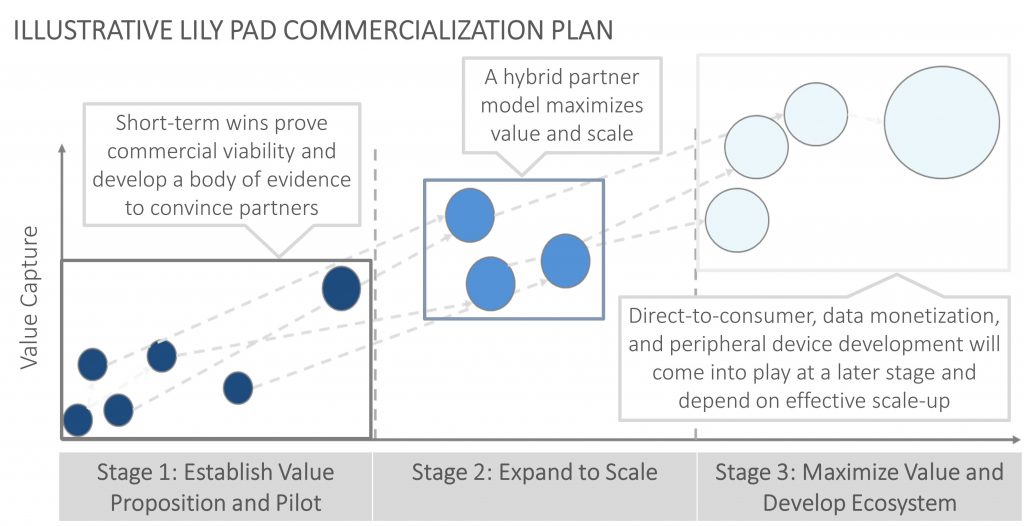

Quantifying our client’s value prop using QUANTIFIED DESIGN™ innovation allowed us to build a much more robust go-to-market plan for their product.

We would contrast this engagement with a project where Newry worked with a client from the beginning to develop their overarching strategic focus – based on both qualitative and quantitative methods – and then worked iteratively with a team of designers to guide the client’s innovation efforts.

By adopting a market-insight-driven perspective early on and refreshing quantitative insights regularly throughout the product design and development process, our client avoided a last-minute scramble to define the key value props that the market would support. We also bypassed the redundancy problem often associated with the handoff between the strategic marketing function and the design thinking function by working closely and continuously with our client’s design firm partner. The result was the successful introduction of an award-winning, first-of-its-kind product – built on a platform that has continued to create value for the client.

What no one at Let’s Make a Deal seemed to realize at the time was that by analyzing the door “problem,” one could construct a strategy that would on average, bring better results. Remember our contestant forced to choose between keeping their selection or switching to the remaining door? Mathematicians have shown that choosing the new door offers better odds of success (2/3 chance) as opposed to keeping along the current path (1/3 chance).

Design thinking is one good way to better understand what might be behind the doors of innovation opportunity. But using it alone, or without a clear connection to other strategic marketing efforts, can create blind spots – and cause significant problems if the value prop is misaligned with market dynamics.

On the other hand, intertwining design thinking with a strategic and quantitative effort will lead to a more powerful understanding of the real size and definition of your opportunity. While this augmented process of “QUANTIFIED DESIGN™” may take slightly longer, it provides a nice middle ground between picking direction based solely on gut instinct, and a full-blown central R&D strategy – and increases chances of success by leading to products more aligned with the organization’s strategic intent, the end user’s desired experience, and a value prop connected to a business case.

So, go on… pick door #3.

Find out how Newry can help your organization decide where to focus. Have conviction and validation about the opportunities you’re pursuing.