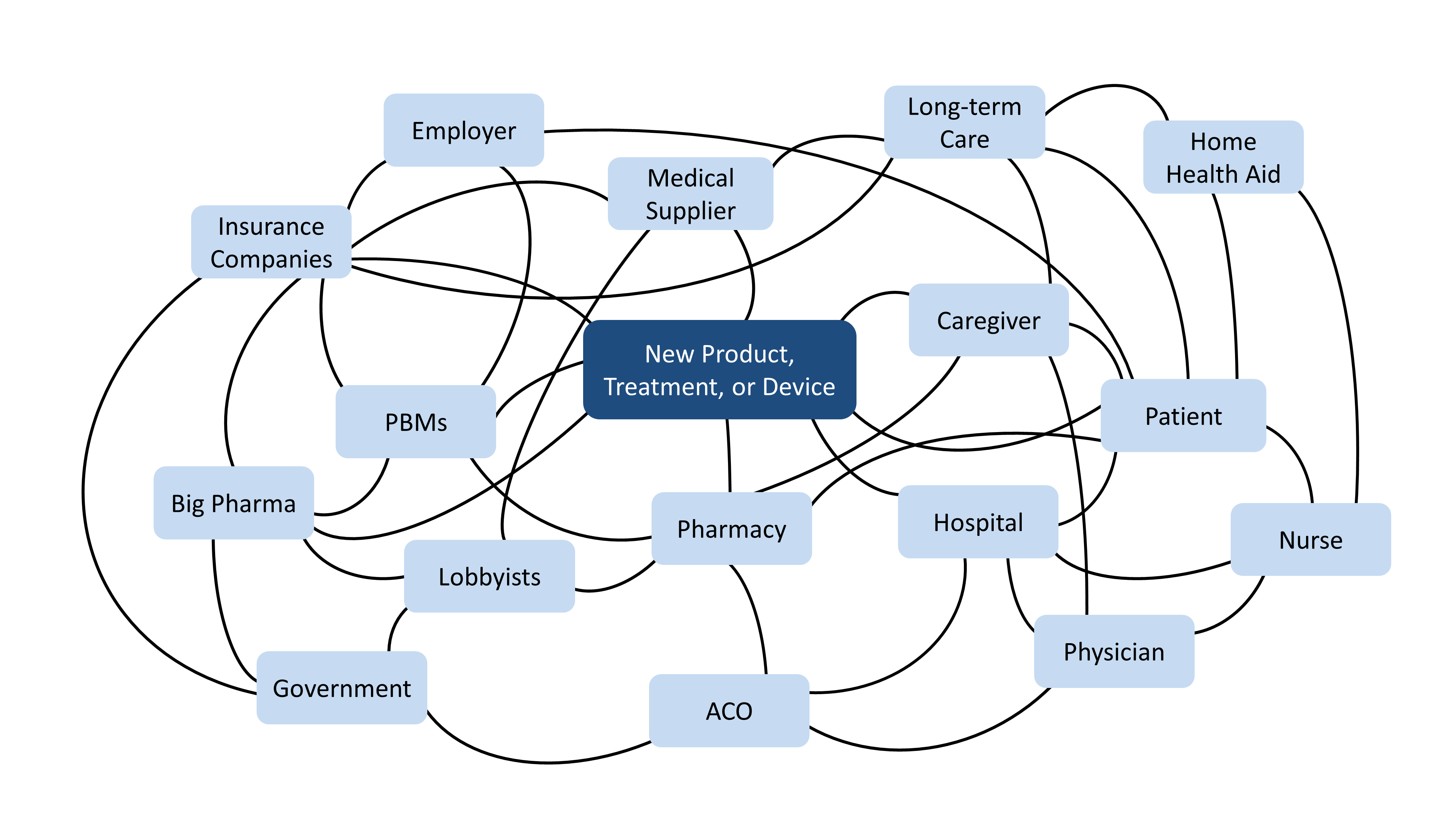

In a post last year, we discussed the complexities of the healthcare ecosystem and offered some thoughts on how to navigate the challenging path to new product commercialization for medical technologies. Specifically, we suggested that understanding the various players in healthcare – in terms of their relationships to each other, their relative power and influence, and their likely reactions to a new product – is critical to achieving your goals.

But this perspective is only part of the puzzle; to succeed, you will need to ask yourself, “How will my product or innovation make money?”

To some, this question may seem cold, or even mercenary. Shouldn’t a healthcare product serve the patient above all else, and shouldn’t we be focused on patients who are desperately in need of better treatment? The reality is, in our system, the patient has very little power and very few resources – and while designing the perfect product to meet their needs is an admirable endeavor, it ultimately doesn’t mean anything unless you can also guarantee them access, which comes from a robust, economically viable vision for how your product will go to market.

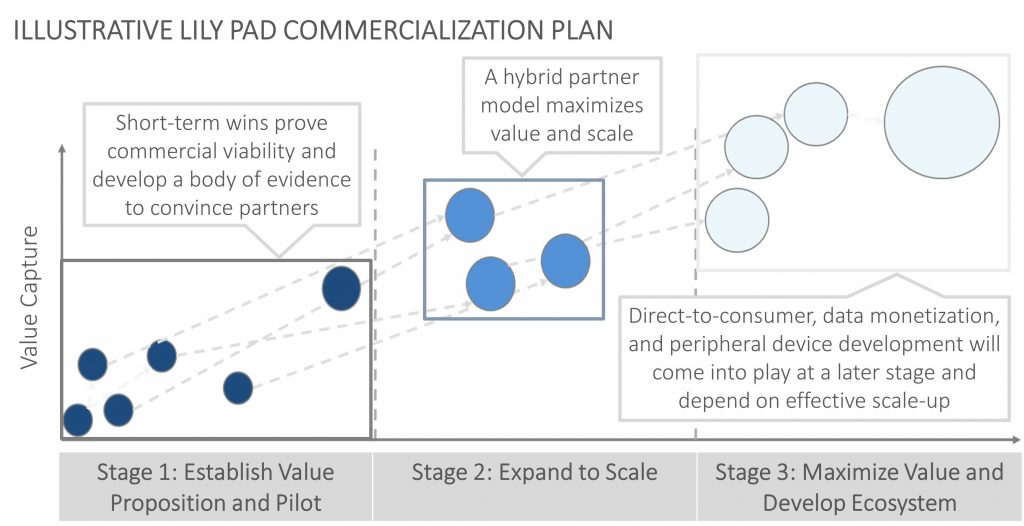

Building this vision has three steps: first, you need to determine what types of value your product can provide; second, understand who will pay for that value and what level of proof they will require; and third, hedge risk by leveraging multiple sources of value.

1. Determine what types of value your product can provide

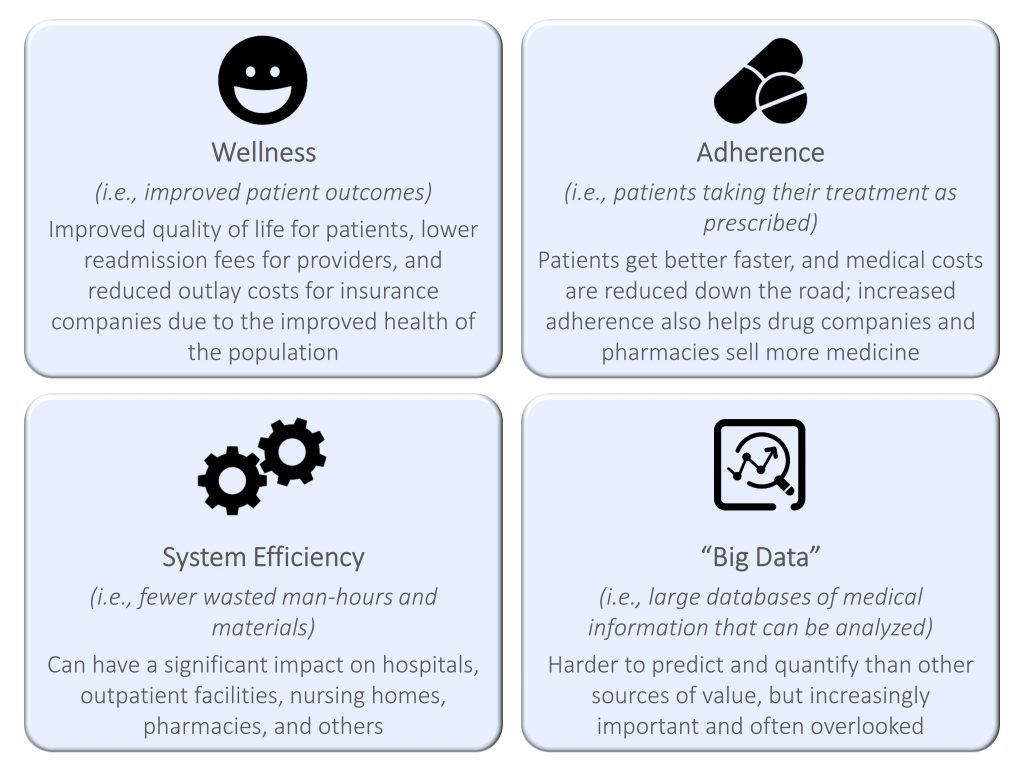

There are several different kinds of value a healthcare product or medical technology can provide, all of which hold varying levels of importance to the different players in the ecosystem:

2. Understand who will pay and what proof they require

In most instances in healthcare, the purse strings are controlled by the payer. Healthcare products live and die by whether insurance companies choose to cover them – or not. Unfortunately, working through insurance companies entails many complications, including a high burden of proof for efficacy, a bias towards solving costly problems that may or may not align with patient-critical ones, and issues with the internal budget setting and economics of the insurance companies themselves.

For example, although wellness benefits have clear value to insurance companies, payers won’t reimburse wellness-focused solutions without a high standard of proof. This is because 50% of insurance companies’ costs come from 5% of their insured lives, so they obsess over cost-benefit equations for that 5%. If your device can stop Jane or Jim from landing back in the hospital for an expensive procedure, they will listen – but only if you can provide data from longitudinal studies with robust randomized patient populations and multiple disease states, all to ensure the benefit you’re claiming isn’t just “regression to the mean” (i.e., patients getting better of their own accord).

Even if you can prove your device works, you still may not be out of the woods. Reducing costs – by, for example, preventing a patient from going to the hospital as frequently – does not do an insurance company any good if it happens 5 years from now and the patient has switched to a different provider. Payers want to see a benefit within their planning and budgeting horizon, which is often 1-2 years out.

Getting payers to reimburse based on adherence can be even trickier. Although solutions correcting patient behavior are thought to save healthcare costs over time, they also increase the number of prescriptions filled and follow-up visits scheduled – which puts a greater economic burden on the insurance company in the short term. Furthermore, while improved adherence has been tied to improved healthcare outcomes, this correlation is not well quantified or understood. Thus, if you lack the evidence to prove a long-term net positive outcome, or if the payer simply lacks the vision to appreciate that future result, it may be tough to capture value from them.

3. Hedge risk

Healthcare product commercialization is a long, difficult road requiring significant investment to prove efficacy, especially if you’re counting on payers to support your solution (which, if you want to achieve any significant volume in sales, you probably are). The good news is the payer-centric business model isn’t the only way to capture value in the healthcare ecosystem, and there are many other ways to get in the door. Ignoring these additional sources could make for a much riskier and less profitable commercialization strategy.

When Newry tackles these challenges, we look at a couple of general strategies that help capture multiples sources of value and use the power dynamics of the healthcare “knot” for your own ends:

- Lilypad Strategy: We’ve discussed this concept in previous blogs, but the basic idea is to de-risk an investment by pursuing multiple achievable value capture mechanisms in parallel and using those to pay for increasingly larger programs. In healthcare commercialization, this can mean launching multiple diverse pilots for your device or product, giving you access to different value streams and allowing you to test different value propositions to various customers. For example, for a medication management device that could have benefits in wellness, adherence, and system efficiency, you may want to launch pilots with insurance companies, integrated delivery networks (e.g., the VA and Kaiser), nursing homes, and pharmacies. Each pilot program would prove a different source of value. While launching multiple pilots may be resource-intensive, it de-risks the overall investment in case any one source of value fails.

- Partner to access value streams you can’t reach: Because different players often see different benefits from the introduction of a healthcare device or technology, partnering is often necessary to maximize value capture. A device company could partner with a pharmacy benefit manager (PBM) and drug companies to capture adherence value while also partnering with payers and providers to capture wellness value. Some organizations have already combined to be able to capture multiple sources of value. United Healthcare’s acquisition of the PBM Optum is an example of this type of consolidation, along with CVS and Aetna’s proposed merger. Additionally, integrated delivery networks are set up to combine the payer and provider functions and therefore may be an ideal partner to capture multiple value streams.

The dynamics of the US healthcare system are such that the core mission of medicine – healing the sick – often gets lost in the shuffle of relationships and transactions between powerful entities and entrenched economic realities. For healthcare product and technology companies, navigating this complex landscape can be a source of tremendous frustration, especially when a truly valuable user-focused innovation fails to launch due to its incompatibility with, for example, insurance company economics. And yet, that very complexity also allows for creative solutions that may not be available in a more straightforward industry – and by planning ahead during product development, it is possible to leverage some of this market’s most Byzantine practices to make life-changing innovations accessible and affordable to patients.

Find out how Newry can help your organization move smarter to move faster. Get traction in your market.