Designing Early-Stage Market Success

The basic function of the wristwatch has been the same for hundreds of years: display the current time (and maybe the date or moon phase in fancier models). This premise holds true for digital and analog watches, $50 and $5000 watches, watches that are waterproof up to 30 meters and those that can withstand a 300+ meter dive. Across the board, and over centuries, the general concept has remained the same.

Today, however, the watch industry is being disrupted by the smartwatch, a wearable device connected to the wearer’s phone. The smartwatch market is young, but new entrants like Samsung, Apple, and Sony are already gaining significant ground against storied brands like Tag Heuer and Rolex – smartwatch sales are projected to grow 18% in 2017, while the traditional watch market has been suffering since 2015.

Mechanical watchmaker John Tarantino calls the Apple Watch “a mini supercomputer with a leather strap on it.” (The Verge)

Of course, the value proposition of Swiss watchmakers goes beyond time-telling (craftsmanship, aesthetics, etc.), and tech companies may never unseat the role that traditional watch brands play in, for example, the luxury space; nevertheless, the success that these new players have realized indicates that there may be a seismic shift underway. So, what does this mean for traditional brands who fear losing share to this new technology and wish to remain competitive by developing their own smartwatch offerings?

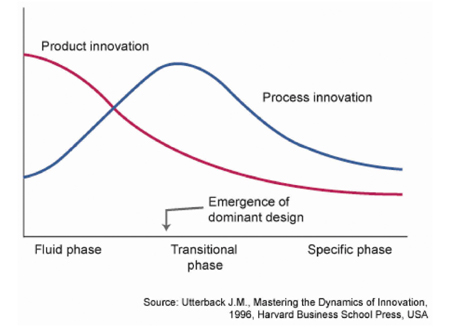

The Utterback-Abernathy model of dominant design, developed in the 1970s but still highly relevant to technology-based innovation, begins to provide some insight into this question. The central idea of the model contends that, in a new market (or an existing market experiencing significant change), a specific technology will emerge as the ideal solution, which will then be adopted industry-wide as the “dominant design.”

This process happens in three phases:

Fluid phase – Many companies enter the market with many different designs, jockeying to maneuver their technology into the dominant position. Other companies watch the market, but wait to enter until the frenzy has died down.

Transitional phase – As time passes, one technology or design emerges that suits the needs of customers particularly well. The creator of this product is, for the time being, the only company capable of meeting market requirements, and essentially has a monopoly until other firms begin to mimic their solution.

Specific phase – In the last phase, the market has embraced the dominant design, which gradually becomes a commodity. Companies attempt to beat each other by offering essentially the same product with better features or for a cheaper price.

Once the fluid phase has ended, companies must adopt the dominant design in order to remain competitive in the market.

So, how does this relate to smartwatches?

Suppose that Apple, the current leader in the smartwatch innovation race, continues to increase their market share and firmly establishes their technology as the dominant design. In this scenario, companies like Samsung and Tag Heuer would need to stop attempting to develop a differentiated offering and start modeling their smart wearables after the Apple Watch. It may not sound as exciting as creating the winning technology, but in many cases, it’s the only way to survive – once the fluid phase has ended, companies must adopt the dominant design in order to remain competitive in the market.

It’s not all bad – second movers who can move quickly still have plenty of opportunity to provide unique features and gain market share. Take Nike as an example: they determined early on that their Fuel band was not likely to be selected as the dominant design, discontinued the product, and used the money that would have been spent on refining the design to build out software instead – software they have since used to partner with Apple to produce a special edition of the Apple Watch.

If navigating this kind of innovation cycle as a consumer products company sounds difficult, consider what it means for their suppliers. The components and materials companies who serve the Apples and Samsungs of the world face an infinitely more complex landscape of potential opportunities and obstacles – not only do they have to attempt to predict which product design will dominate in order to develop a compelling offering for their customers; they must also attempt to engineer materials that will work with the components provided by other suppliers, and do so at a lower cost and higher level of performance than any of their competitors. With limited insight into secretive customers’ requirements and little exposure to end markets, attempting to innovate for a consumer product technology still in the “fluid phase” (like the smartwatch) can seem like an exercise in pure fortune-telling.

Many tiny, finely tuned components go into the Moto 360 smartwatch (iFixit)

And yet, it must be done – getting spec’ed into a product before the dominant design emerges is both challenging and risky, but getting spec’ed into the winning product after the fact is nearly impossible. If materials and components suppliers want a chance at playing in a potentially major emerging market, they need to place their bets early. Fortunately, there are ways of making those investments and focusing those innovation activities strategically. Nothing beats an existing customer relationship – if they’ve trusted you to solve their problems before, chances are they’ll be willing to come to you again – but other methods (leveraging data science techniques to identify major trends and unsolved problems, developing platform strategies for product development to hedge your risk, cultivating a long-range, adaptable view of a new market to avoid being leap-frogged by competitors, etc.) can offer a leg up as well. Successful B2B innovation in dynamic market spaces is never easy, but with these tools, it can be somewhat less impossible to achieve.

Find out how Newry can help your organization move smarter to move faster. Get traction in your market.