Your core capabilities are almost always the best source of growth. Until they aren’t.

Despite the huge amount of airtime (and blog-iation) devoted to “blue oceans,” “white space,” and “3rd horizons,” we at Newry are conservative in counseling our clients about reaching beyond their core. In our experience, grass-is-greener thinking is often just an excuse for failing to exploit markets where you already are and capabilities you’re already excellent at. Over and over, we hear clients say that “there just aren’t any more good problems to solve” in the spaces where they already play. And over and over, we find new and immediately addressable opportunities in precisely those spaces, simply by looking at capabilities or market context from a slightly different angle.

Recently, however, a client situation has forced us to think hard about why, when, and how to pursue opportunities beyond the core. We still believe that core capabilities are generally under-exploited and shouldn’t remain untapped. But sometimes, leaping into the “Blue Ocean” is the best thing to do – and, in this case, may be the only thing to do. I’ll explain here why I believe these particular circumstances warrant such bold action, and then posit that the key to making that leap lies in challenging and redefining your most fundamental assumptions about who you are and what you can do.

Here’s the situation:

- Our client is a world-class innovation company. They’re not exactly a household name, but in the realm of performance materials, they are an iconic and longstanding player – more than a century old. They have deep technical skills, a very strong balance sheet, and a CEO-driven determination to grow. So, basically, they aren’t lacking for resources or know-how.

- Their core markets are impossibly tough. As mentioned previously, many innovators chronically underestimate or ignore the magnificent opportunities that still remain in their core markets. In this case, however, we believe that our client may have truly tapped out its best capabilities. Most, if not all, of their core markets are decades old, with slowly shrinking profit pools and gradually declining top lines. The stuff they’ve always been good at has become highly competitive and painfully commoditized. And as a result, they’ve been stuck for years in a low-to-no-growth mode.

- They’ve tried every traditional trick in the book. They’ve attempted acquisitions to add revenue, and then an SBU-autonomy-is-everything mode. So far, neither has yielded significant growth. In frustration, they’ve returned to technology-driven organic growth as their desired vector, but even some new-market success entrees have been challenging as global demand has fluctuated.

In short, they are facing a slow, but seemingly unavoidable, decline. Buffeted by a hurricane of technological change, intense global competition, negative growth in their core markets, and a slow but steady transfer of profits to somewhere and somebody else, this company is running out of options.

It was in this context that our client came to us requesting that we evaluate the market potential for a new material they’d developed. This material is fairly similar to their existing products and, at first glance, offered excellent adjacency opportunities for their core business. But as we learned more about the technology – and just how distinctive it is – we realized that our client could have something a lot more important; possibly even game-changing. What had initially appeared to be a modest $10-50MM opportunity for a new performance material started looking more and more like a multi-hundred-million opportunity for a whole new category of product.

Just one problem: in order to really capture this opportunity, our client might have to do something they rarely do: invent, make, possibly even sell a complete product. It will be very difficult and feel very dangerous to them. We think they can do it, with their broad capabilities, plentiful cash, committed top management, and growth aspirations – and, frankly, we don’t think they have much of a choice, given the grim outlook in their core markets – but it won’t be easy, and it will require a big leap of faith.

Sometimes, leaping into the “Blue Ocean” is the best thing to do – maybe the only thing to do.

There’s an instructive parable for this state of affairs in Edgar Allen Poe’s 1841 short story, “A Descent into the Maelström.” Drawing on ancient Norse myth, Poe describes a pair of brothers trapped aboard a ship caught in a maelström – a huge ocean whirlpool. As Poe’s story goes, “driven by the worst hurricane man could imagine,” the ship is slowly but inexorably dragged into the whirling ocean vortex. One brother clings to the ship’s mast, hoping to be saved by the familiar objects and apparent stability of the ship. The other brother observes that “the larger the bodies, the more rapid their descent,” and deduces that he would be better off abandoning ship. So, he grabs a barrel and leaps overboard.

Of course, the brother who clings to the mast perishes. And the brother who jumps is thrown clear of the vortex and saved by another ship.

In the case of our client, the temptation is to take this new material and keep doing with it what they’ve been doing with the rest of their portfolio. In other words, grab the mast and hang on. But we suspect that, to survive the larger maelström in which they’re embroiled, they’re going to have to take bold action. And in order to do so, they’re going to have to challenge some of their most fundamental ideas about what they need to do to stay alive.

More specifically, they need to challenge assumptions about what their enterprise is and isn’t, what they can and can’t do. These self-imposed, fundamentally limiting assumptions come in all forms, and there are thousands of them – think of them as the organizational version of the silent, internal monologue that’s always telling you, “No way.” We’ve discussed previously how making the wrong assumptions about a market opportunity can get you into trouble, but making faulty assumptions that fundamentally limit your ability to act and innovate is just as dangerous.

The reality is that doing something really big, really special, really innovative is more often about escaping the limits of how you perceive yourself – the walls of your ship – than it is about the opportunity itself. For example:

- We’re a materials company. We don’t make products. Truth is, many of the most successful product companies started out as materials companies, and virtually every successful industrial company began doing something much less ambitious than it now does. 3M started out selling abrasive grit, not Post-it Notes. Corning started out selling flint glass, not optical fiber. General Electric started out making light bulbs, not jet engines. Apple started out making hobby computers, not ubiquitous smart phones. Walmart started out as a local discount dime store, not a $450B retailing behemoth.

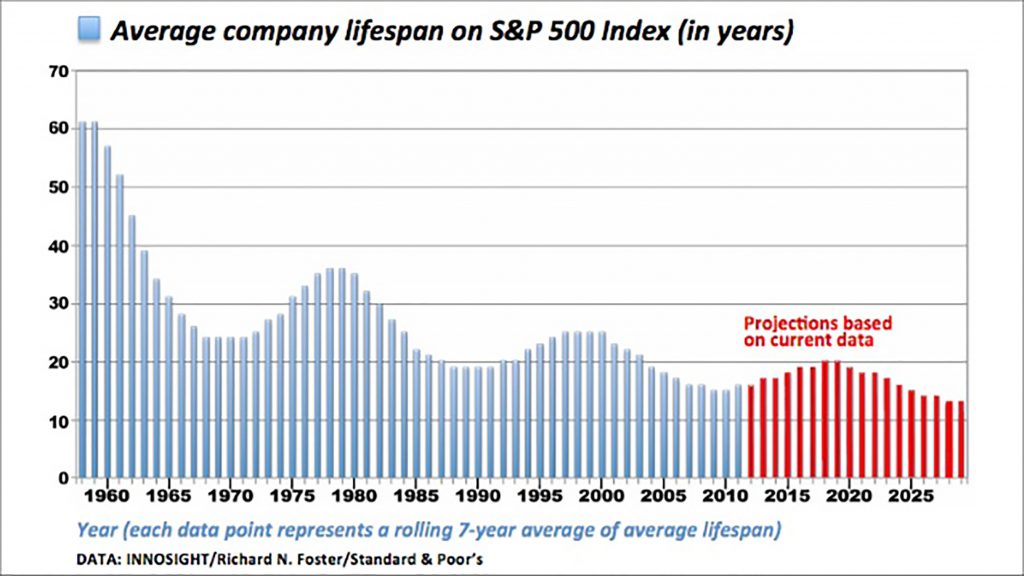

- It’s too risky: Have you considered the alternative? A fascinating piece of analysis by Clay Christensen showed that over the last 70 years, the average lifetime of an S&P 500 company went from 60 years in 1960 to just over 15 years in 2016. Companies are disappearing at a furious rate. Think about it: where are Bear Stearns, Kodak, Saab, Pan Am, WorldCom, National Semiconductor, Enron, Circuit City, Lehman Brothers, Arthur Anderson, and Blockbuster, to name just a few? These companies were household names with secure futures. They were safe vessels in a storm – until they weren’t, and disappeared into the maelstrom of 20/21st century industry.

- We don’t want to compete with our customers: Sometimes relevant, but the industrial world of 2017 is a $100 trillion economy. That’s 100,000 billion-dollar markets. You really can’t find room in 100,000 billion-dollar markets to maneuver around current customers? If not, don’t worry – some start-up will.

- Our business units are successful and focused – we don’t want them to take their eye off the ball. Often good advice, which is exactly why IBM established a separate SBU to commercialize the PC – because the PC violated one of IBMs principal paradigms, i.e., the pre-eminence of the mainframe, and would have died an ignoble death as a project within one of the conventional SBUs.

- We don’t have the paths to market: Maybe today. But in just a little more than 20 years, Amazon has managed to create – from scratch – paths-to-market for $130 billion worth of products. Apple sells billions of dollars in music via iTunes, a path to market that didn’t exist 20 years ago, while the conventional path to market – the 1970s record store – is nothing but a distant memory.

- That’s a great opportunity – but we just don’t have the capabilities to tackle it: Almost always, companies, particularly large companies, are far more capable than they think. But they’re stuck in their paradigms, and often make fundamentally faulty assumptions about what they can and can’t do. Remember, the surviving brother in Poe’s story didn’t just jump overboard and hope for the best; he found an object – a barrel made for storing rum – that could serve as a life preserver. In addition to his bold leap, he made a radical yet simple adaptation of a current product’s (the barrel’s) current function (storing rum) – and turned it to a totally new purpose.

3M was an abrasive grit company – mining and minerals – until it imagined sticking its expensive dirt to paper and, later, adhesive to cellophane and, later yet, semi-adhesives to small pads. Corning was a glass housewares company, until it heard about transmitting light down a fiber. In these cases and others like them, the transformation took time, and in some cases a lot of money; but in the end, these industrial giants escaped from their own paradigms, siloes, stovepipes, and narrowly defined focus areas. They got out of their own heads. They recognized that they were slowly succumbing to the maelstrom, and leapt headlong into the wide, blue ocean.

None of them are clinging to the mast of a sinking ship. How about you?

Find out how Newry can help your organization find high-value options for growth. Expand your pipeline before it runs dry.